Friday. It’s spring and you’re free. Free to go home, to nap and shake the exhaustion of a week of work and early mornings from your bones. Free as well to walk around your city, sleepy and dusty and hot and noisy.

You take the metro to Atocha—they changed the name of the station 15 years ago to Estación del Arte, but in your brain and in your bones it will always be called that: Atocha. You can hear the far-away rumour of the trains in Atocha Train Station, the whisper of the wind against what’s left of the trees of the Paseo del Prado to your right, the song of the cicadas, and people talking, always loud.

It’s 3pm and it’s March and you’re tired. The metro was full and you ended up in a corner. You still feel sticky, and when you step outside on the street and take off your mask, you blink under the glare of the sun. It shines white and high up in the sky, and you still remember when spring felt like spring, when summer was just another season and not the only one.

Back then, cars were still permitted to drive through the Paseo and around the Station and down to Delicias and back to Conde Casal. You remember the smell—burnt rubber and the spicy stink of burnt diesel—and you remember how the pollution felt on your hair and on your skin and in your throat. You remember going back home after a day out in the city with your friends during the summer months, and jumping into the shower, your skin tacky with sweat and pollution. You remember as well the itch in your throat and fighting against the need to cough, the way your chest spasmed; it’s one of those things you can’t quite believe you ever saw as normal.The mere act of existing in a city shouldn’t make you sick.

And the cars were loud—they were so loud. They clogged the roads and streets of Madrid and reached into its heart, filling everything with noise. An ever-present hum, droning and low, that you could feel in the pit of your stomach and in the hinge of your jaw, right under the ears. You don’t miss it. You used to think that maybe you would, but you don’t.

It’s late, and you’re hungry. You haven’t eaten lunch yet. You see fast food restaurants and tourist traps and overpriced cafés. There is a plastic kiosk that’s probably almost as old as you are on the corner of the Cuesta de Moyano. Someone is listening to music, and you don’t know the song, or the artist, but it feels familiar. It’s early spring in 2031 but it’s also August in Madrid ten years ago.

That’s what gives you the idea–the kiosk on the corner.

You know this sudden craving is nothing more than nostalgia. You long for what’s forever lost…

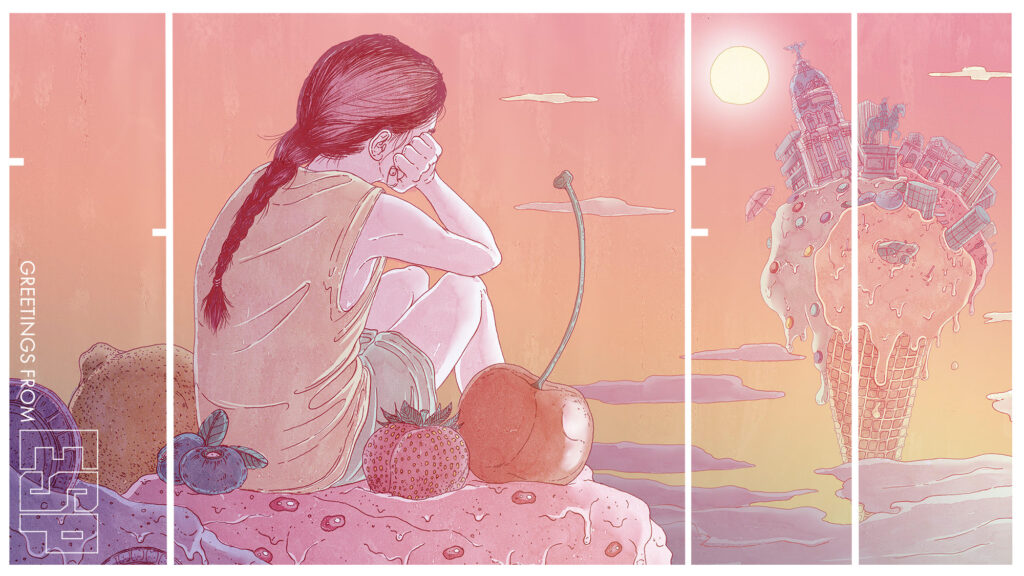

You can see the big blue sign from where you’re standing. It tells you that they sell ice cream there, but not the kind you like–the kind you suddenly crave with all your strength. Actual gelato, creamy and sweet and cold. You shouldn’t—you’re an adult. You should just go home. You know this sudden craving is nothing more than nostalgia. You long for what’s forever lost: you wish you were ten, fifteen years younger than you are now. You may have been aimless, but at least you hadn’t lost all hope in the future.

You turn your back on Atocha Station and the Paseo del Prado and walk towards the Reina Sofía Museum. Now and then a bus drives around the corner, blue and white against the clear summer sky. They screech their way up and down the road like the remnants of a long forgotten age—the only vehicles on the road, the kings and queens of Madrid.

Atocha Street is long and steep and the trees that line it are still too young, their shade spotty and weak. They’re half-dead: it’s too hot and too dry for them to thrive, and their spindly branches reach, naked and pale, towards the sky.

You still remember when they suggested ‘planting’ synthetic trees, like plastic Christmas trees, but sadder and uglier. You hated that idea and you know you weren’t the only one. Now, however, you can’t help but think that maybe it would have been a better option. Better a patently fake tree than witnessing the slow and torturous death of dozens of real ones.

The road is empty, the tarmac so warm you think you can feel it from the sidewalk, the cold A/C from the shops blasting your legs. You aren’t the only one walking around. Now and then you cross paths with a band of tourists, red and overheated, their sandaled feet slapping against the street, phones in hand and looking around wide-eyed. They don’t actually see you, but you see them and you wonder: You know why you’re here, out on the street, under the summer sun—but do they?

You take out your fan from your bag, the loud rattle of its wooden ribs when you open it, reassuring and familiar. You fan yourself and keep walking, the hot, dry air hitting your sweaty face. It doesn’t do much, but it’s better than nothing. The narrow, winding streets that branch from Atocha Street beckon to you.

But you know it won’t be that easy. There’s an art to finding a place to eat in Madrid at 3pm on a Friday. You mastered it years ago, the ability to choose the right place, to wait just long enough, to check with friends and ask for recommendations and know when to give up and go somewhere else. But you’re too tired, and the pilgrimage it would require feels as hard as climbing Everest.

…you still remember […] when summer was just another season and not the only one.

You reach Antón Martín Square. The old market to one side, now a sushi place—a couple of years ago it was something else, but you can’t quite remember what it was—and the old pharmacy with its toy hot-air balloon hanging from the façade of the building, hovering over the Antón Martín metro station.

Huertas Street is to the right, the Antón Martín market and Santa Isabel Street to the left. Madrid stinks when it’s hot, always has, always will. But underneath the stink of piss, of dirty water and cheap frying oil and rotting garbage, you can smell someone cooking something garlicky further down Santa Isabel.

You keep walking. You never remember what this street is called—but you remember when shops that flank it sold fabric and wool. Most of them had been there for decades, but one by one gentrification and time have made them disappear. Only a couple survive, and you dread the day even those left now will fade away. You walk in the middle of the street, under the shade of the young, sickly trees, and you stare at the new cafés. Most of them are franchises, Granier and La Rollerie, and you realise that you didn’t think to check that the place where you’re going is still open.

Jacinto Benavente Square. There used to always be a line of cars waiting by the semaphore on the corner. Now they’re gone, but the area is still chaotic. There are tables and umbrellas everywhere, and most of the former are full despite the heat. Once the cars were gone, the bars and cafés that line the square moved in.

There’s a bus waiting further down the road, a line of people slowly sweating to death under the flimsy shade of the bus stop—you can empathise.

You take a left, the way familiar after so many years. You walk past the closed cinema doors. You can see that the lights are on inside, the art deco façade dirty with pollution and time. There is a soup kitchen next door, and there are people already waiting in line despite the heat.

The gelateria is further down the street. It’s mediocre. It’s also the only one that’s still open. By now they know your face, and the person behind the counter greets you while you look at the flavours behind the glass, as if you didn’t know what you were going to choose already, as if you had not been thinking about the lemon sorbet and pistachio ice cream cone you were going to buy for the better part of an hour.

You eat it inside. The place is more or less empty. There are a couple of tourists talking quietly over gelato and iced coffee at the table in the corner. The A/C is on. You sit at a free table and look through the glass storefront at Tirso de Molina Square. At first sight it looks just like it did ten years ago—but you know your city well. You know that it’s changed. They used to sell flowers there—the flowers are gone. There were always people drinking and talking on the benches but they took away the benches a few years ago, and now the people are also gone.

The sun beats down on the square, and when you touch the thick glass with your fingertips, you think you can feel the heat. Ice cream trickles down your hand and you lick your wrist.

Lemon, sharp and not too sweet. You sigh. The longing hasn’t disappeared, but it feels lighter. You hide it away in a corner of your mind along with all the other things you usually don’t have the time or the strength or the will to think about.

Madrid is still Madrid: it survived the Civil War and it survived the 2004 bombings. It will survive climate change and gentrification, but sometimes you think it will be despite itself.

María Bonete Escoto (Elche, 1993) is a Spanish writer based in Madrid. She participated in the climate fiction anthology ‘Estío. Once relatos de ficción climática’ (Episkaia, 2018), has published the short climate gothic novel ‘No hay tierra donde enterrarme’ (Episkaia, 2019) and has a short story in the anthology ‘El Gran Libro de Satán’ (Blackie Books, 2021). She writes non-fiction about the relationship between videogames and culture as well, and you can read her work in Heterotopias Zine, Revista Manual and Nivel Oculto. She is on Twitter as @flowersdontlast.

Elena Galofaro Bansh is an illustrator and animator from Italy based between London and Milan. She recently graduated from the Royal College of Art and she’s now working as a freelance artist for international clients. You can find her on Instagram.