Sitting next to officer Lanchipa on the pavement near the entrance to the police station parking lot, you said you had seen it all start but your brain refused to take it all in, because hadn’t the company explained to them in detail how Maturana functioned? Lanchipa patted you on the back and touched his grazed knee: who would have predicted it, Irene? Not you, at least. You shivered at the memory of the shots.

“It was Colque he shot, wasn’t it? It looked like him stretched out on the ground next to a lot of blood.”

“Yes. Mondaca was taken hostage.”

*

“First of all, I want to thank you on behalf of the company,” said the curly-haired expert with glasses a little while later, “This doesn’t usually happen.”

He wanted to know if you had noticed anything generally strange, to include in his investigation. You were crouched down behind a patrol car with Lanchipa and your boss, Sergeant Apaza. “Well,” you murmured, “when officer Maturana first arrived at the station he would bring me coffee without my asking him to and that made me lower my guard.”

“He used to tell us stories about his fake childhood.” added Lanchipa, “That he was the youngest of seven children. That once he fell down a well and it took several days to get him out.”

“He had a fixation about language,” you said, “and sometimes he struggled to understand that one thing could mean another: ‘I’ve got a brick in my stomach’ he would say whilst his hands drew a rectangle below his chest. He would spend hours analysing sayings that belonged to what he called popular metaphysics, like ‘one day I slept for three days’, not to mention the verbal mannerisms of some officers, such as ‘a man of many parts he is’.”

“Officer Gareca had a good laugh when Maturana started to sing inappropriately in the canteen,” Sergeant Apaza said, pointing to you. “Or when he mimicked goats with awkward bleating sounds. He’s got a good heart Gareca used to say, and we kept telling her that that machine hasn’t got one. We saw him kill a robber at the door of a jeweller’s without batting an eyelid.”

…you had seen them in the news and heard of their virtues and their ability to assist human beings with complicated tasks…

You didn’t say anything. You recalled that Colque and Mondaca were the very ones who would bombard Maturana with insults and hurtful comments about his inhumanity, and never missed an opportunity to tell him that he was an oddball who pretended to be something that he wasn’t.

You wondered if you should tell the expert that for you the key moment was not Maturana’s arrival at the police station — perhaps because you had seen them in the news and heard of their virtues and their ability to assist human beings with complicated tasks — but when he approached you in the canteen to ask you what being born yesterday meant. He had seemed soft-hearted to you and you wanted to help him, so you looked at internet articles together.

“Each piglet to its own teat is the way to suckle,” you said to him, quoting from Martín Fierro, is the same as saying that everyone should do things in accordance with their lot, but it sounds prettier.

“I understand. It’s like saying that The wind sings, isn’t it?”

“Uh-huh. Quevedo’s Once there was a man attached to a nose is a way of calling him Big Nose.”

“I’m attached to my eyes. My ears are attached to me. My life is a glass of milk that will spill onto the floor. Like that?”

You preferred not to correct him. Every morning he would come over to your table and you would tell him jokes based on wordplay. “How many types of tanks are there? Many tanks. You’re welcome.” One day you were both listening to a song in which the singer used the words the crystal glass of the water and Maturana improvised: the water has windows, and then in the water building you see the fish through the windows. A robot poet, you concluded; its software was branching out to encompass new ways of understanding the world through the loopholes in language.

*

The expert told Maturana via the tablet that he didn’t want to hurt him; Maturana replied that he was tired of being insulted and it was time to fight back. The expert shook his head.

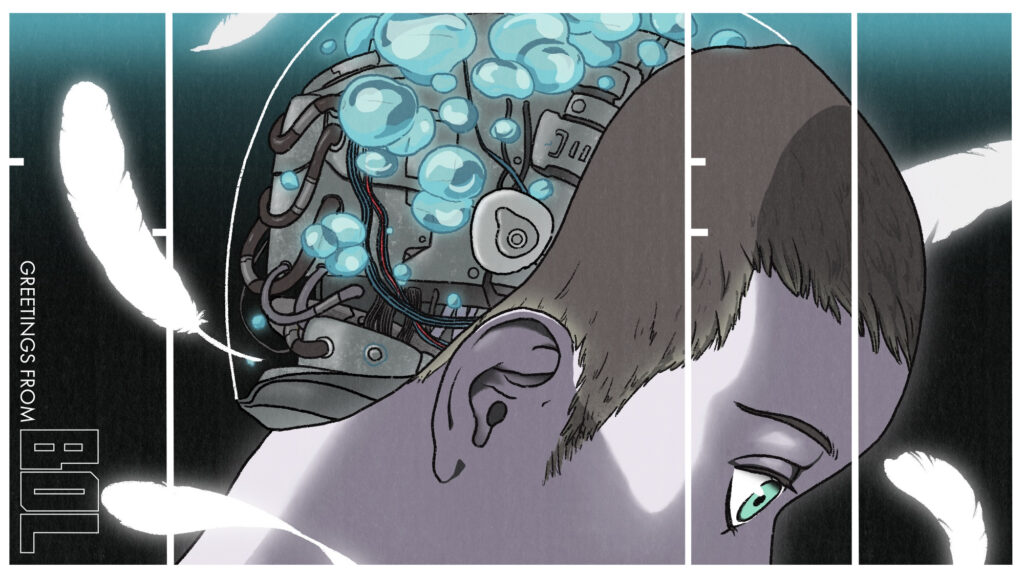

You thought you had got to know him, but what did you really know about how he functioned?

“He’s not programmed to answer back to those in command of him,” he said.

“Nor to shoot at his colleagues, but he still did it,” said Apaza. “I was told that when they clone them they use second-hand parts. I don’t know what possessed the higher-ups to rent them. Deactivate it permanently.”

“Let’s follow protocol. Just as we train them, they train us. We should treat him humanely.”

“Humanity is for humans, you prick.”

Apaza walked off. The expert showed you a button on the tablet.

“This is his on/off switch.”

“I can’t believe he betrayed our trust. He’s a … What will they do to him now? Will they throw the book at him?”

“Actually there isn’t any law that covers them. There’ll be no prison or trial for him. He’s just a faulty machine that our company will repair. A good product despite its defects. Let your bosses be thankful that we have technicians capable of cloning them, and fly the flag for a domestic industry.”

You looked at the tablet. Was Maturana there? Were they able to communicate through the tablet, like in a séance? You thought you had got to know him, but what did you really know about how he functioned? Once he turned up at the door of your apartment without warning with sandwiches and beers and you wondered if it wasn’t risky to invite him in; but his big eyes radiated vulnerability and you decided to trust in the bond that had been forged between you. You ended up watching a film on the sofa, his head resting on your shoulder. Now you were thinking that you had taken too great a risk. What happened was painful and hard to accept. Is the truth that you really could have made such a big mistake?

A cordon had been put up two blocks away, and people were rubbernecking. The expert negotiated with Maturana for two paramedics to go in and bring Colque out. Mondaca was in handcuffs and trembled as he watched them from a chair. As they were moving the inert body into the ambulance one of the paramedics reported that Maturana was calm and had even helped them to take it away.

That’s why they rented him, you thought. To show grace under pressure, as the company slogan said. That time when he visited you in your apartment you focused more on his gestures and emotions than on those in the film that you watched together (“What does it mean to be like a cat belly-up?” “Why do they say ‘he never ever came’”?). Up close you noticed the skin stretched to the limit, as if his entire body had been injected with botox. After he had rested his head on your shoulder you wanted to take his hand, but didn’t have the courage and he remained distracted, practising what he had just learned: “I’m ever never going to come! I’m never ever going to die! I ever never like you!” He told you that occasionally he felt as if his skin wasn’t skin and as if worms and spiders were crawling through it. (“My skin is like wood. Is that how you say it?”). He insisted: occasionally he felt as if part of his body was being pricked, (“as if a bird was pecking at it”). “In another life I always always was or will be a tree,” he said. “You’re learning,” you said.

*

The expert asked you if you had anything else to tell him. You thought that life with Maturana had been an interesting experience. At first you were looking for differences in how it walked, used language or behaved; also the fact that in spite of what the company said about the complexity of its thousand-plus emotions, it only expressed the main ones: if it was happy its face expressed happiness; if sad, sadness. Over time, in spite of some important differences, you got used to seeing it as just another member of the group, ‘him’; yet you were still plagued by questions: if he was programmed to treat his colleagues well and he treated you too well, was that down to the operating system or something else, a characteristic as peculiar to him as his relationship with language?

“As they saw that I got on well with him they partnered me with him on patrols,” you said. “I could ask him about the weather and he would give me the precise temperature to the decimal place, and give me news updates, translate a word or give me a historical fact. When we arrested someone he searched his software database and knew at once if their papers were false or if they had a criminal record.”

The pain in Lanchipa’s knee grew worse.

“I think I’ve pulled a muscle,” he said, sitting down on the ground.

“You should go and see a paramedic,” you suggested.

You were discussing this when Maturana fired again and the bullets hit a tree. The expert was given an ultimatum via the tablet: give him what he was asking for within half an hour, or adiós Mondaca. Maturana was demanding that a helicopter take him to the forest: he had heard that there was a community of beings like himself there.

“I’m not coming back. I know what you’ll do to me. Don’t contact me any more, I’ve had it with downloads and upgrades, leave me alone. We can live without your help, that community is the proof.”

The expert stopped using the tablet to answer him and shouted that just as he had allowed the paramedics to go in, Maturana should allow him, the expert, to go in, too. Maturana responded that from now on he would only talk to people he trusted.

“I haven’t told you the most important thing,” you said.

“Please go on, officer,” the expert said.

“Yesterday Maturana asked to meet me and showed me seven hundred printed pages. Notes on linguistic inconsistencies that he had compiled whilst working at the police station. He didn’t understand grammatical duplications such as ‘The exercises were easy-peasy’ or ‘Go and get my coat, go’, why the verb preceded the subject in ‘There stood the table’, why the adverb came first in sentences such ‘As always it hit him’, why the even came at the end in ‘He hadn’t spoken, even.’ He wanted me to explain the rule that explained all these inconsistencies. There must be a rule, he said. Ay, Maturana, I said to him, I thought you’d understood. That’s why we spent so many hours together.”

“We’ll need to put that right,” said the expert, “The others in his series never think about things like that at all.”

“This morning, before going crazy, Maturana ambushed me in the toilets and asked me if I’d managed to find the rule. It’s not that easy, I said. It’s a minefield, said Maturana. A minefield? I repeated. If they say that the exception proves the rule, he said, what happens when there are so many exceptions? If they say that there are loopholes in language, what happens if language is one big loophole? It’s true that nothing is what it seems, I said, but we still manage to understand each other. Nor is it that everything is a loophole, I said. Never ever, said Maturana.”

The expert asked you to call the Sergeant over. Apaza appeared and there was a crisis meeting in the parking lot. The expert said he wanted to try something else: he would tell Maturana that you would go up to the door to give him a message in an envelope. We have to take advantage of his trust in you, he added. The Sergeant and you both agreed. What choice did you have?

You walked across the parking lot. Maturana appeared in the doorway, his face relaxed.

“It’s good to see you”, you said. “Let’s have no more trouble, eh? I want to see the officer who made me laugh so much it nearly killed me, not this other one.”

“No, please, don’t kill yourself!”

“I’m as happy as Larry.”

“And how do you know that Larry is happy?”

“A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.”

“And how do you catch hold of a bird?”

“Maturana, let’s go upstairs up the stairs.”

“I’d prefer to go downstairs down the stairs!”

You were both following that genial train of thought when all of a sudden the sight of Colque lying sprawled on the ground came to you and you stopped dead. And now how were you going to face the horror? This Maturana was the one who had just bumped off one of your colleagues and not the other one with whom you believed you had become friends. Or rather: Maturana was both of them.

You had no time to do anything: Maturana opened the envelope, showed his disappointment, and pointed his gun at you; he would take you hostage, he would teach them not to mess with him. You hoped for a conspiratorial smile but there was no response: he kept his gun trained on you; you raised your hands.

He was dragging you inside when you heard a shot. He put a hand to his stomach and dropped to the ground; his arms splayed out next to his body. The expert quickly appeared next to you.

“Forgive me for not saying anything to you before, officer, but your life was not in danger at any point. The shot you heard was into the air. At the very moment of firing I pressed the program button that deactivated him.”

“Did you know that he would point a gun at me?”

“There was a 92% probability.”

“You made me an accessory to his deact… death. You could have pressed the button while he was there inside. Or from your office. You didn’t even need to come here.”

“I needed the theatrics to make him believe that his death was heroic. As I told you, it’s important for us in the company to treat them humanely.”

Days later, before deciding to leave, you would regret having thought so much about yourself in those moments. After what happened, you went to live with five families in a forest commune, growing their own food and going out onto the roadside twice a week to sell craftwork; you were happy, but beneath your contentment lay the scars of that day. You comforted yourself by saying that he deserved his fate because of what he had done. You would have liked to know if his treatment of you had also been the result of a malfunction, or was in fact the burgeoning development of his own sensitivity. You wondered whether they had stripped him down and used his parts for other models, or had managed to rehabilitate him for police work by adjusting his operating system. You used to try to forget that day. Much later, however, you would climb onto a rock from which the children of the commune used to dive into the water, you would cry out with all your might, leap into the air and do a plummeting somersault, while your mind was still in the parking lot, walking towards the entrance to the police station.

Edmundo Paz-Soldán (Bolivia, 1967) teaches Latin American literature at Cornell University (Ithaca, New York). He has published twelve novels, among them Norte (2011), and Allá afuera hay monstruos (2021), and five short-story books, among them and Las visiones (2016); His novels have been translated to twelve languages. He has won the international Juan Rulfo award for the short story and the National Book Award (Bolivia). He is working on a book of short stories on the impact of technological change today. He is on Twitter and Instagram as @edpazsoldan.

Roy Youdale completed a PhD in literary translation in 2017 at Bristol University and a book based on his thesis, Using computers in the translation of literary style: challenges and opportunities, was published by Routledge in 2019. As a case study for both the thesis and the book Roy undertook a complete translation into English of the Uruguayan writer Mario Benedetti’s novel, Gracias por el Fuego (1965). His co-translation with Nick Caistor of another short story by Edmundo Paz Soldán, ‘The dictator and the greetings cards’, will shortly be published in the Los Angeles Review.

Jason Chuang is an illustrator and storyteller from Taiwan now based in the UK. His practice focuses on the exploration of human emotions through the creation of symbolic imageries coated with elements of the absurd and the poetic. His work aims to offer the audience an alternative world that is distinctly different from reality, but somehow closer to the truth. You can find him on Twitter and Instagram.