Over the years, Storythings has worked on a number of projects about identity and related issues like credit and pay. We always look for routes into what are pretty complicated topics by finding personal stories or perspectives that help pick apart what they mean to people everyday. We’ve found using formats really focuses us on what we want to say – like this Zoom discussion (approx. 45 minutes) in response to Lavanya Lakshminarayan’s story and its themes of identity, technology and the future.

We were lucky enough to be joined by Malavika Raghavan, a lawyer and inter-disciplinary researcher working on Data Protection & Privacy, Inclusion, Technology and Consumer Protection in Finance; and Emrys Schoemaker, a researcher and strategist at Caribou Digital interested in the interaction between digital technologies and social, political and economic change. They covered so many issues in their conversation with Storythings’ Director Anjali Ramachandran, we really hope you enjoy it and feel as inspired and enriched by it as we did.

Other Storythings projects about identity have included reinventing the report for Omidyar through serialised emails and using audio laid over images to protect the identities of vulnerable people; using animated video and narrative through a series called The ID Question for our Gates Foundation publication, How We Get To Next; and documentary film for Experian, which we directed through a pandemic. If you’d like to explore how we could help you approach issues of identity, get in touch!

The following is a summary of highlights from the Zoom Discussion.

Anjali: What do you think is actually possible in ten years’ time when it comes to technology and identity in India given what’s happening now?

Malavika: I thought [the story] was a wonderful approximation of life as a privileged young woman in Bangalore — from the obsession with coffee to workplace anxieties and the choice to disconnect from reality.

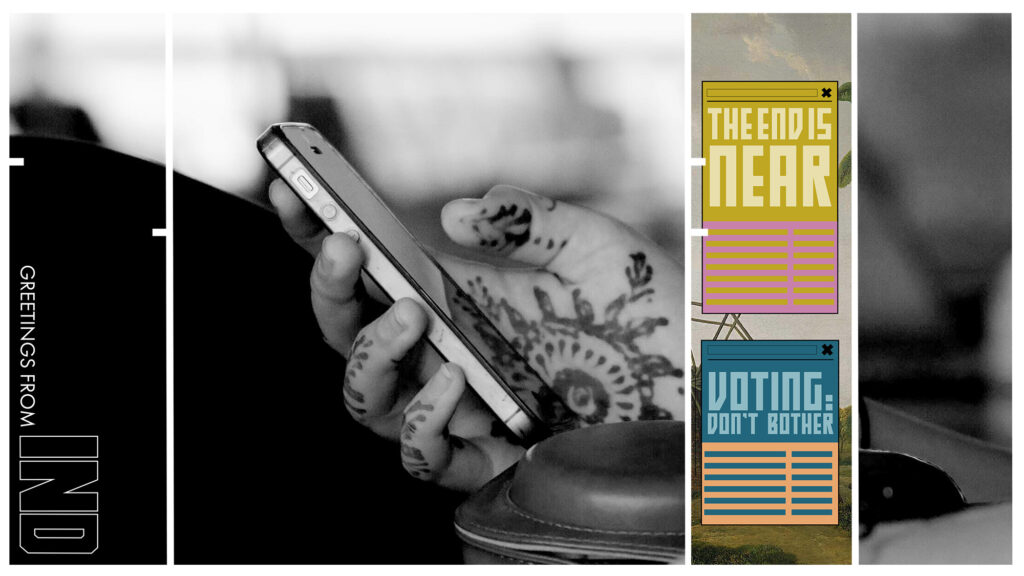

The deeper question it left me with is something that I think we are starting to experience in India — what would it be to live in a world where you don’t know how to keep your secrets secret?

How does that play into anxiety and mental health? How do you navigate the world? How much can you escape what is going on?

Emrys: It raises an interesting question about identity – identity in a social sense, and in a kind of ‘personal character’ sense… It is not about technology but about who we are as individuals.

I suppose the underlying question that this story raises for me is: where does control lie and what does control mean over what data is collected about us, and how that data is used?

Fundamentally, how much control do we have over what we see around the world? And how what we see shapes what we want to do and who we want to be?

I think these are really interesting, challenging philosophical questions…

And I don’t know if fundamentally, we have ever had that philosophical question — how should you show someone the world, if the only world they see is what you decide that they see?

Malavika: When control over data also means control over perception, especially as we go into augmented reality, it’s not merely that you’re controlling what a person gets to see and what they don’t, but also how they see it.

And I don’t know if fundamentally, we have ever had that philosophical question — how should you show someone the world, if the only world they see is what you decide that they see? Do we show them a road you don’t want them to go down?

Anjali: In the context of national identity systems, and identity generally, I think we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention or talk about Aadhaar — the world’s leading national identity project — in terms of the amount of data collected in India. How much does Aadhaar really take into account the realities of the people on the ground, and the ease, or lack of, with which they have control over the data that is being collected about them, and the way that data is being used?

Malavika: When you’re building a public service application, taking a top-down approach means that the people [at] the top (socially, politically, economically, technologically) are the ones that are built for.

People have a sense of distance [from] the state. It’s seen as a gatekeeper. It’s just another bureaucracy for people to get into. So someone [up] here has said, you need X, Y, Z in order to access X, Y, Z. Then the lower down you are, the more difficulties you will face in order to fit with the mental model of the person up there.

I think in the world of data protection, increasingly, we agree that control really is fairly meaningless. Because if you are subject to all these cross-linkages and complex algorithms (which even the people who build them can’t quite understand what they will do) there is no way you’re going to be able to say, ‘I want this algorithm to have this associated rule-mining approach’.

If you have these deep entrenched power relations, I think one of the easy […] institutional design fixes, is to start to do things which keep [the] system accountable conducted by a biometric audit; [and] release aggregate statistics of transactions, especially transaction failures; and have analysis of where these failures are happening and who are they happening to.

We are all living in an increasingly digital world, and digital data is increasingly personalized — personal data can make things better suited to us, but can also put us at much greater risk of targeted exclusion and inclusion.

Emrys: We often forget that identification by its very nature is intended to be exclusionary. You don’t design an ID system that supports open access to a service or right for entitlement. Because if it’s completely open, why do you need to identify who this person is in order to determine whether they have access or not? We should actually be talking, I think, much more about identity exclusion as the primary function that these systems play.

If we link back Aadhaar to Lavanya’s story, we see that these different ways of tracking who people are, and tracking certain attributes of this person — their health status, or their geographic location…, or their welfare, their entitlement to certain welfare distribution —all of this is about saying: can we say no, actually? Can you not have sugar with your coffee? Are you not actually entitled to this distribution of rice or gas or whatever Aadhaar might be enabling for a particular individual…

Identification in the story is primarily identification based on passively generated data points. The behaviours that this individual is doing are captured, exploited, monetized.

Aadhaar reflects a very different kind of legal relationship between the individual and the state.

I know that Aadhaar isn’t a reflection of citizenship, and therefore deals with status. But it’s a reflection of residency and it’s used to manage the relationship between the individual and the state…

I think we need to start thinking about […] the worst case scenario — what happens if this data falls into the hands of people who are going to use it for the worst intents possible?

At the same time, we also need to […] understand better tools and technologies that might … enable the benefits of identification technologies but mitigate some of the harms.

We are all living in an increasingly digital world, and digital data is increasingly personalized — personal data can make things better suited to us, but can also put us at much greater risk of targeted exclusion and inclusion.

One of the efforts to address the concerns around Aadhaar has been to try and open source it’s products. We need to recognize the limits of open sourcing technologies. It’s not the closed or the proprietary or open source nature of the technology that may be the issue in question. Power is still going to be able to be exercised through MOSIP as much as it does through Aadhaar or through AIRE, the Huduma Namba or any other of the national ID schemes that we see in place and are increasingly concerned about.

Anjali: What are the positives we can look forward to when it comes to the future ? What things should people that are building these technologies, and these [identity] systems, actively need to think of when they are looking to build for a population… to build a technology that is fair, neutral? What are the positive things that are happening, whether it’s open-source or not, that we can take forward… in the next 10 years to build identity devices, technologies that are truly inclusive or… at least not intentionally exclusive?

Emrys: …all identification technologies reflect a relationship between the identifier and the identified. I think that is really important to recognize because it enables us to understand that it’s the dynamics of that relationship that are critical to thinking through ‘how do we design technologies that achieve a particular goal’?

If […] we are talking about trying to ensure equity in terms of control and power, then I think one of the great things digital technologies enable is transparency – [digital technology] enables everything to be logged. There is huge potential in making the way identification systems, both state-based identification systems for individuals but also social identification platforms and services, far more transparent.

One of the great things about the Estonian ID system is that every individual can look at their record and see who has accessed their data. They don’t necessarily have the control to stop it, but [they] can at least see who’s accessed [their] data, and hopefully why.

I also think there are huge efficiencies to be gained. We shouldn’t get seduced by the siren call of efficiency as an unquestionable good.

One of the things we found doing the research around Aadhaar was how actually those frontline bureaucrats, as individuals who manage access to certain welfare entitlements […], are able to make sure that if your biometric fails, or if I’m sick and I have to send my brother […], that they are able to negotiate the rules to ensure that the spirit of what’s entitled, or meant, is realizable, without being constrained by the rigid ‘computer says “No”’.

There are innovations in the world of cryptography, of technological design, that can mitigate some of the potential abuses for technologies. For example, MasterCard and ICRC are investing in researching and putting in place technologies where biometric data can be encrypted. A token of that encryption is then used as your identifier, and that limits the access to that biometric data, which can be a source of exclusion or targeting.

I think there are also really big innovations happening in the world of decentralized, or federated, databases and systems.

Malavika: I think the issue with identity, and pitching it right, is similar to privacy. They are related concepts because there’s a zone of privacy that we don’t want in the law; but it’s similar to that of identity in that, being invisible is exclusion, but being so visible that you will not get services is also exclusion.

In its best form, a proper identity system can visibilize people, while maintaining their control over their graded information sharing.

I often find it hard to say graded information sharing because what we’re talking about here is ‘who gets to know what about us’ and ‘who decides what needs to be known’? Because knowledge is the ultimate gatekeeper —especially in these very knowledge-based societies.

At the highest level, I think [what] a good identity system could do is think carefully at the design stage of whether something needs to be gated.

One of the positives of the Aadhaar system is that it had a ready-made contactless payment system for India; and most underprivileged, low-income people were able to get access and get included through the system.

A good ID system would also include feedback loops. One thing we saw is that as transactions jumped — like double, tripled, quadrupled – in the months after the lockdown, transaction failures also quadrupled. Millions were coming to one provider because of biometric authentication failures. Another was coming from silver downtimes between the bank and the payment switch.

A lot of these failures, or these highly engineered systems, many of them are not in the control of the individual at all. A lot of that has to do with good systems, technical systems, cryptography, cybersecurity…

The last thing I want to say is around design and operationalization. [When it’s] something that’s totally not required — whether it’s your street level bureaucrats saying ‘I want your Aadhaar to give you a school application’ —there are some legal tests which have come up, which also are good design tests, at least in India. But you see it happening in every country. So, there is a theme here we can draw from — which is to ask ‘Is it necessary?’

And then, when you say ‘It is necessary’, you make the determination.

Then you ask, ‘Is it legitimate? Do you need this? Is it legitimate for the purpose?’

And then finally, if it is necessary and legitimate, to ask, ‘Is it proportionate?’

Does that coffee maker in ‘Your Cup Runneth Over’ really need to know your health status records?

Whichever order you want to do that in, it will make [design and operationalization] stronger.

The final thing I will say — we need much more [qualitative research] because fundamentally if that person is not at the table, when the system is being designed, then it’s very hard, ten years down the line, to [rectify that omission]. So it is a good idea to have every kind of user at the table, and at least most majority users at the table.

Anjali: It just brings to mind how constantly evolving the subject is with all the changes that are going on, technology obviously, but then regulation as well.

I want to thank you both very much for your time, and I’m going to read out the last paragraph of the story because it’s quite poetic and we touched upon it today in the beginning where we spoke about the philosophical aspect — Lavanya says:

You’re oblivious to the role you play on this planet, but it’s an important one. You’re a grain of sand on this massive subcontinent, being knit together with other specks of humanity like you. You’re being spun into a perfect sphere of glass. Transparent, empty and practically invisible. Beautiful and easy to shatter if required.

Go on, then. Take a sip of that perfect cup of coffee. You’ve earned it.

Anjali Ramachandran has a background in digital media, strategy and innovation. At Storythings she works on strategy and exec production for clients including Experian and Nesta. She is passionate about diversity, equality and inclusion and is a co-founder of global women in tech network Ada’s List. She also writes the Other Valleys newsletter looking at creative and tech-related news from emerging markets. She has worked across India, the US and UK.

Malavika Raghavan is a lawyer and researcher studying the impacts of digitisation on the lives of lower-income individuals in India. She is currently undertaking doctoral research at the LSE in Information Systems and Law. She founded and headed the Future of Finance Initiative at Dvara Research in India until 2020, where her work addressed new challenges for consumer protection. She remains an Advisor on the Initiative’s International Advisory Board, and also serves on the Steering Committees of the Digital Identity Research Initiative (DIRI) at the Indian School of Business, and the Data Governance Network at the IDFC Institute, India. Previously, she has worked as a solicitor with a global law firm and completed stints with social impact investors in the UK. Malavika holds an MPhil in Public Policy from the University of Cambridge, a B.A., LL.B.(Hons) degree from the National Academy of Legal Studies and Research (NALSAR), Hyderabad.

Emrys Schoemaker is a researcher and strategist looking at digital transformation in contexts of social, institutional and economic change. Emrys is currently research director at Caribou Digital and a visiting fellow at the LSE in London and at Cornell Tech in NYC. He has conducted research into mobile, internet and digital identity technologies in Asia, Africa and Latin America for governments, bilateral and multilateral donors and foundations as well as non-profits and the private sector. Originally from the UK, he recently moved back to NYC from Amman, Jordan.