Shares: So. What Do These Numbers Really Mean?

As the saying goes, if you love something, set it free. Or at least, post it on your socials so your friends can see it and you can get some sweet sweet engagement. Sharing is the most sought after and valuable of all digital metrics, because it is really three things bound up in one action – attention, value, and social status. The Net Promoter Score – one of the most popular audience research survey tools – is based around a single question that has the same kernel of truth bound up in it – Would you recommend this to a friend? This is a powerful signal because when we share something with our friends, we’re staking some of our own social capital on it – we’re saying something about ourselves, and how we’d like others to see us.

Why should I care?

What’s the big picture?

Social networks combined the two, giving us the opportunity to share perfect copies of culture, but also to give it a spin with our own comments, re-contextualisations or performances. We’ve always done this, of course, but before social networks these behaviours happened in bars, classrooms, our homes or the office. The rise of social networks meant that the hidden world of sharing hinted at by the Net Promoter Score question was now visible to all. Sharing became the key metric for impact – if someone shared your content, it meant they had not just seen it, but valued it enough to risk their social capital by sharing it with their friends. As academic Henry Jenkins said in his landmark series of essays on how ‘viral’ culture works – If It Doesn’t Spread, It’s Dead.

So what does this all mean?

When I worked at the BBC in the early 2000s, my team commissioned some research on what drives people to physically participate in an event like a political march, or a fundraiser in the workplace. We started with the assumption that the cause, brand or celebrities involved in the call to action were most important in driving people to actually participate in something. Our research showed that, in every case we studied, the most important trigger was not any of these – it was whether participation presented an opportunity for our existing micro-social networks. For example – a woman running a Comic Relief event at her work was a big fan of the TV show, and believed strongly in the charity’s impact. But the trigger was much more local – they’d recently recruited new people to her team, and she saw the event as a way for them all to get to know each other.

This shows the risk of deriving meaning from sharing behaviours in aggregate, and designing campaigns that directly ask users to share content. Our motivations for sharing are never because of a brand’s call to action, but because we have seen something in a message that gives us an opportunity to create value for our immediate micro-community. This doesn’t mean that we don’t often have the same kinds of motivations for sharing, but it does mean that a company or brand ultimately has much less influence on sharing than we’d like to think. The best way to get people to share something is not with a direct and specific call to action, but by creating something a bit looser, so that users can find their own motivations and value in it.

Tell me something I don’t know

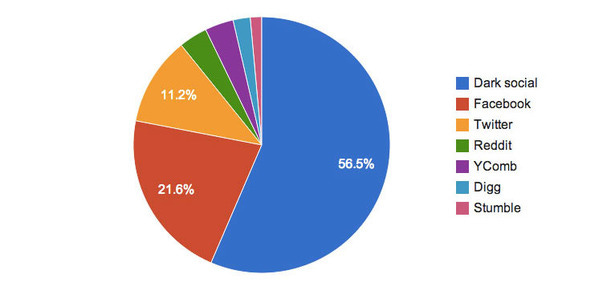

But Madrigal found a lot of direct traffic to articles that had long and complex URLs, meaning it was highly unlikely that users had typed them in or bookmarked them. His experience on pre-social web message boards told him that this was more likely to be from users sharing links in non-public networks that couldn’t be measured by their analytics tool, Chartbeat. Working with the team at Chartbeat, he found that this ‘Dark Social’ traffic was more than double the traffic they were getting from Facebook, and an average of 50% of referring traffic to articles, even for articles that had ‘gone viral’ on platforms like Twitter or Reddit, as this sample chart showed:

Looking across a broader selection of Chartbeat customers, they found that Dark Social represented 69% of referral traffic, even higher than The Atlantic’s numbers. The takeaway from this is that public social sharing is a form of publishing – it’s not just sharing with our micro-communities, but potentially with a large public audience as well. This has a radical effect on what we share on these platforms, especially over the last few years, as public social platforms have got more toxic. We actually share a lot more in private group spaces, where we can have more control over how we present and contextualize the content we’re sharing. So if you’re building a campaign based on social sharing, planning for Dark Social sharing is twice as important as public social sharing.

Give me some numbers

Sharing is rooted in deep emotional needs, and that is why we should never take it for granted. If we don’t do the work to create content that helps people show who they are, and feel connected to their friends, then we can’t expect people to share it.