To a colleague

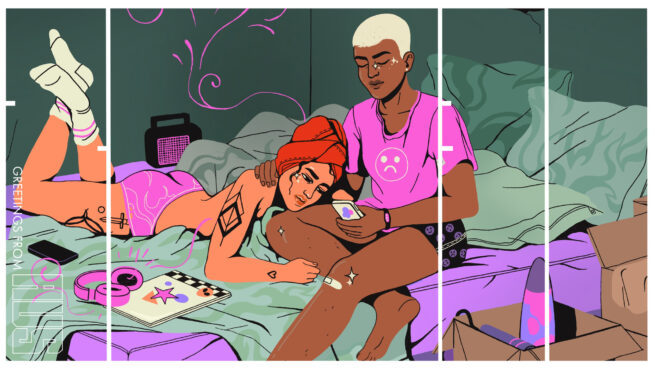

Ellen van Neerven’s story is about two climate migrants in Australia, who’ve been forced to abandon their home due to climate change.

Australia’s land areas have warmed by about 1.4°C in the last 110 years, according to the climatologists at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and annual temperature changes are above natural variability in all land regions. This temperature rise has been accompanied by a rise in the frequency of extreme weather events like heatwaves, fire weather, heavy rainfall and flooding. Sea level has risen at a rate higher than the global average, while sandy shorelines have retreated in many locations.

These trends are projected to continue in the coming decades as temperatures rise further. Sea level rise is projected to continue in the 21st century and beyond, leading to coastal flooding and shoreline retreat, by hundreds of metres in some cases, while the intensity, frequency and duration of fire weather events are projected to increase. Also projected to increase are heavy rainfall, river floods, heat extremes, sand and dust storms, marine heatwaves and ocean acidity.

Different parts of Australia are likely to see different changes. In the northern monsoon region, average rainfall changes are uncertain. But an increase in heavy rainfall and river flooding is projected by the middle of the century, alongside a decrease in cyclone frequency but increase in the proportion of severe cyclones. In Central Australia, there is a projected increase in heavy rainfall and river flooding, and greater warming is projected than in coastal areas under all future scenarios. In Southern Australia, a reduction in mean rainfall is projected, particularly in the cool season, as well as an increase in aridity and the frequency of droughts. These projections carry greater confidence in the southwest of the country, due to its already-high aridity and drought risk. In the east, there is a projected decrease in cool season rainfall, but more extreme rainfall events overall, as well as a projected increase in droughts.

The IPCC hasn’t yet published its latest report on Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, i.e. what this means for humans – it’s in the works and due to be published in early 2022. But in 2015, a team of researchers led by Andreas Backhaus used a model derived from the OECD’s International Migration statistics to show that a 1℃ increase in average temperature is associated with a 1.9% increase in migration flows between 142 sending countries and 19 receiving countries, and an additional millimetre of average annual precipitation is associated with an increase in migration by 0.5%.

The scientific literature (e.g., Nicholson, 2014; Baldwin and Fornalé, 2017; Bettini, 2017; Constable, 2017; Islam and Shamsuddoha, 2017; Suckall et al., 2017) consistently highlights the complexity of migration decisions and the difficulties of attributing causation. Climate change-related factors sit alongside religious and political persecution, pollution, natural disasters and economic factors like house/land prices and job availability in the long list of reasons that feed into any decision to migrate. This makes it difficult to definitively prove that any large-scale migration is ‘caused’ by climate change.

Nonetheless, the recent Groundswell report, published by the World Bank, projects that 216 million climate migrants globally may be forced from their homes by climate change impacts by 2050. Australia, in particular, is expected to receive many migrants from surrounding Indo-Pacific countries in the coming decades because of geographical proximity, existing social networks and the fact that it already has migration legislation that focuses on the Pacific.

Undullah Street is a timely reminder that those hundreds of millions of people have complex thoughts and difficult feelings all of their own, and urges us to treat them as humans, not as mere statistics.