Three in One

Ten Years of Tumultuous Change and Nothing Has Changed

By Hisham Bustani, tr. Nariman Youssef

Those years that you have lived through since the pandemic first hit your country have not been ordinary years.

The economy dried up and so did your livelihood. As people reorganized their priorities, and as was the case whenever that happened, you were recategorized as a luxury item. Your clientele was reduced to a handful of patients with severe dental pain, and even more severe haggling skills when it came to your fees. You shut down your practice and involuntarily, purely as a side-effect of this nightmare, made a recurring dream come true: you dedicated yourself to writing until further notice. And here you are, sitting down to contemplate your future which has already become your past.

Those years that you have lived through since the pandemic first hit your country have not been ordinary years.

Your phone rings. Your publisher tells you that your new book has arrived from the press and that he’s organizing a number of promotional activities at various venues and book fairs. You don’t really care. Not anymore. You receive your fees in the form of copies from the same book and you no longer have the energy to act as a small-scale distributor, selling them on consignment around the various cultural coffee shops and indie bookstores that couldn’t afford the publishers’ conditions, and which have mostly now gone under because of the state of things. The economy has ground to a halt, people have turned into selfish beasts, and every now then nature cracks her whip, killing many without letting the species perish. The apocalypse that you had imagined as deliverance turned into a form of slow perpetual torture, deliberately designed to cause pain but not kill.

You look out of your window to where the Jordanian Writers Association, which you once headed, once stood. It disappeared in the first of a series of suspicious incidents about seven years ago. Back then, the society was getting ready to wear its golden jubilee as a heavy and rusty crown on its head. “It’s better gone,” you mumble to yourself as you look out on the trees that are beginning to reclaim its place, rearing their heads out of the deep crater that it has become.

Your phone rings. A critic friend asks for another loan that you know he’ll never pay back. He didn’t possess the same cunning that made you, when you found yourself face to face with hunger, end your writerly dedication and instead dedicate your connections to get yourself a workless job at a purposeless division of the municipality called ‘the urban observatory’ which, for inexplicable reasons, has one lone post for a health official that is now filled by you. The critic preferred piece work, juggling projects, working with donor organizations. Until the pieces tumbled, the projects stumbled, and the donors left. He put his library up for sale, then his car. When there were no buyers, he took to carrying the contents of the former inside the latter, parking wherever he deemed to find a high concentration of intellectuals, and turning the car into a market stall. Failing at the wholesale approach, he put his wares on sale by piece.

The critic tells you that his crumbling financial edifice was somewhat bolstered by sporadic assignments he used to get every now and then to proofread the speeches of His Majesty the King, may God preserve him. But the intermediary, with whom he used to go halves on the fees, hasn’t called in a while. He would later tell him – in the course of their half-friendship – that the speeches were now outsourced to the local branch of an international PR firm, which presents the outline and main statements to the royal court for approval, then produces and proofreads the full speech, highlighting key phrases in yellow along with comments about how they should be delivered: gravely, with compassion, with a frown, indulgently, indignantly, and so on.

You will recall this call as you browse through the newspaper, its front page – always, without fail – adorned by the king’s photograph and his news. That’s one thing that hasn’t changed amidst the tempest of change of the past few years. Another is your loyalty to the newspaper, as your friend has pointed out. “It’s like they print it especially for you,” she says, “the last person in Jordan who still reads it in print.” You’re also the last person monitoring the photograph’s transformations. If the custom of publishing one a day has not changed, the features depicted have. Over time, and as the Defense Law that was activated at the start of the pandemic became a fixed condition, the features have gained in comfort, serenity, magnanimity, and of course age.

The three portraits (of the former, current, and future monarchs) that hang on the walls of public departments, local councils, and private institutions, are regulated by a special law: ‘Guidelines for the Use of Royal Portraits, 2014’, published in the official gazette’s issue number 5278, pp. 2302-2396. These portraits too have changed, even while the guidelines have stayed the same. Two of those depicted have grown older and more serene. Gone were the restless years in which the Arab populations rose up then fell. The anxious years inflamed by Donald Trump’s attempts to radically refashion the region ended with his loss in the 2020 election and the founding of his political movement that divided Republican voters, broke the Republican party’s back, and confirmed the Democratic hold on the US presidency until today, unchallenged. Thus, the politics of maintaining the status quo have returned to the Middle East (at least in the Jordanian-Palestinian-Israeli triangle thereof), unchanged: the two-state solution, one of which forever unformed, and nominal refugees, aided by aid agencies to relinquish their right to return.

The portraits had to reflect the renewed state of affairs, so in 2024 – the same year of the suspicious incidents – a state security unit distributed a new set of portraits. The revisions included the late king – and that despite there being no reported changes in his appearance since his death – replacing the portrait that used to show him in his fifties with another in his sixties, in order to realign him chronologically with the neighboring portraits and maintain a continuous image of a political body that is immortal and ceaselessly present in a visual line that keeps recreating itself in the same order, even as the individuals change: grandfather, son, grandson, who eventually becomes a grandfather, with a son and a grandson, and so on, ad infinitum.

And here you are, sitting down to contemplate your future which has already become your past.

You too have aged, by two whole decades in just ten years. But no one hangs your portrait up on any walls. You have no children and no heirloom. Your publications have increased, while your readers have decreased, and you lost your status in comparison to the social media influencers that the royal court hosts in an annual gathering. The restrictions, prohibitions, and embargoes issued interminably by the Defense Law have swelled and multiplied: martial laws passed shrewdly through constitutional loopholes that curtail the constitution from within, forcing you to wonder: “What if those genius minds employed their acrobatic circumlocutory maneuvering articulation skills for more useful purposes? Would we have remained thus, forever falling into a bottomless hole?”

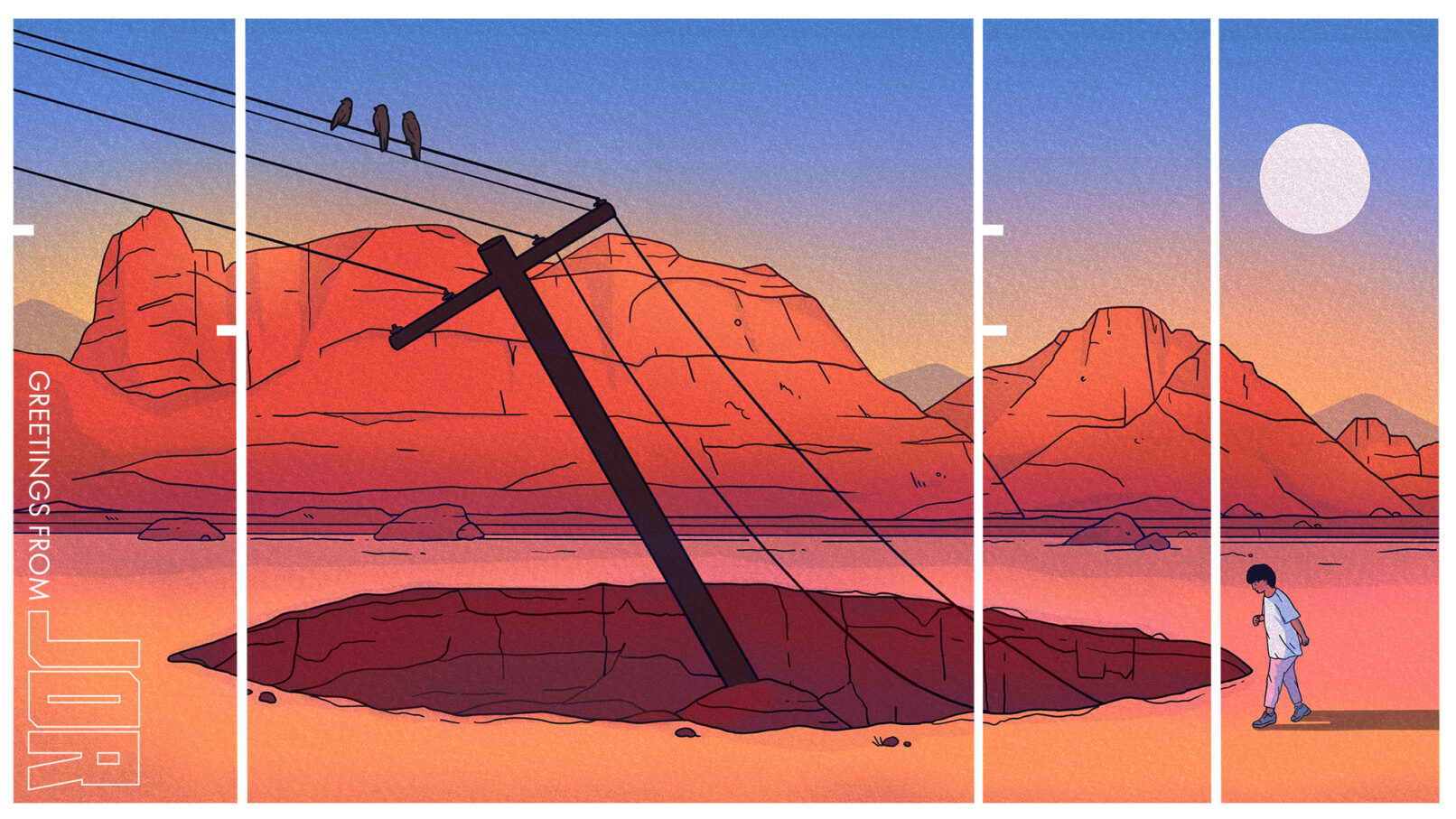

The word ‘hole’ passing quickly in your mind reminds you of the series of suspicious events that are lodged in your memory. You close your eyes and replay the images of that morning when it all started, Wednesday 29 May 2024:

It just suddenly appeared. A deep sinkhole with stagnant water in its distant floor, torn electric cables hanging from its edges, and broken pipes poking out, thick liquid pouring out of some of them and dropping – slowly and slimily – down into the depth.

The first to notice it was a child waiting for the school bus, in the midst of the opening and closing of schools that followed fitful decisions contingent on the state of the pandemic. The night’s darkness lingered still and the building stood at the end of a cul-de-sac, making it difficult to notice what had occurred. But the sound of the neighborhood’s birds, which had – inexplicably – decided to gather in the hole and launch their morning chirping there, resulted in an unusual echo that led the child to look, his jaw to drop and his eyes to pop out in amazement when he saw what had befallen the building of the Jordanian Writers Association. That was what the child told the special committee that was formed by a number of authorities to investigate. Among those was the Urban Observatory Department where you were still new, but owing to your former position as the head of the affected association, you were immediately assigned to the mission.

The putrid stink that rose out of what used to be a creative cultural institution did not trouble you when you visited the site. A few years after the initial spread of the pandemic, face masks had become a daily fixture. The multiplying virus strains hadn’t stopped, turning the number appended to the name of the disease into a bad joke, as the years rolled on further and further away from it. And while the mask’s pressure on the nose is irritating and suffocating, you have found that there is a certain pleasure to derive from watching people’s eyes framed by such face covering. It allowed you to delve into their revealing depths, just as your gaze delves into the depth of this sinkhole.

The day was spent in debates among the various departments that made up the special committee: public security, the governorate, the Engineers Syndicate, the Mukhabarat, and a number of departments from the municipality. By the time the shape and form of the committee was agreed, to begin work on the following day, another building had disappeared overnight, in the same way, leaving behind the same scene. This time it was the Museum of Jordan. Over a week, other disappearances followed, each leaving behind a deep crater: Abdul Hameed Shoman Foundation and Library, Darat al Funun, the National Gallery of Fine Arts, the Artist Syndicate, and the Plastic Artists Association. Although the Ministry of Culture was evacuated of its staff and content after the third sinkhole, it did not disappear, not the following day, nor on any other day that has followed since.

With the exception of the staff who worked in those places, and some students who used the halls to study away from overcrowded homes –and enjoy the heating in the winter, the air-conditioning in the summer and free internet all year round– no one really noticed their disappearance, nor did their absence affect the ordinary course of things in the country.

Well, actually, an artist protest march did set off from the hole where the Artist Syndicate used to stand, demanding the allocation of a new base and calling on the ministry of culture to support their sinking sector. The issue was quickly resolved with the Defense Law directive no. 34 for the year 2025, which decreed the absorption of unemployed artists into the cadre of sanitation workers in the municipality, with the implicit understanding that their wages would be paid without them having to attend to the job. This and the two other organizations were forgotten about, not unlike an earlier, more powerful and significant Teachers Syndicate before them, which had been disappeared in 2020 by a court order, even if its building stood intact. Gradually all mention of that syndicate faded from public and media debates, like it had never been.

Well, in fact, the government offered the Writers Association (to the exclusion of its counterparts) a new base in a building that used to house a nightclub named after the female protagonist of The Thousand and One Nights. The nightclub had collapsed along with the economy, following closures, argileh bans, and a 9pm curfew imposed specifically on establishments ‘of that kind.’ Unpaid rent piled up until the occupants were forced to leave. Coincidentally the building was owned by the same municipality that put the artists on the sanitation workers payroll, and they offered the writers the location of the former nightclub for their new premises, rent-free for three years in return for restoration work. The writers, naturally, did not have the funds for the restoration work, so they turned down the offer and, with that, lost the right to recover their loss.

Your phone rings and startles you out of your reveries. You sit up quickly, rustling the newspaper that was spread over your slumbering body. You read the date – Saturday 25 May 2031 – and see the picture of the king, wearing a smile and his military uniform, under a large headline: 85 Years since Jordan’s Independence, Achievements on the Rise and Progress Continues. A similar headline above a similar photograph stands out in your memory, celebrating, in the exact same words, the centenary of the establishment of the Jordanian state, ten years earlier. You ponder how the years vanish as they move forward, just as your life and writings simultaneously vanish and add up, akin to those buildings vanishing, their mystery still unresolved, and to the tumultuous changes that blow away time but don’t change much.

Hisham Bustani is an award-winning Jordanian author of five collections of short fiction and poetry. His work has been translated into many languages, with English-language translations appearing in journals including The Kenyon Review, Black Warrior Review, The Georgia Review, The Poetry Review, Modern Poetry in Translation, World Literature Today, and The Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly. His fiction has been featured in The Best Asian Short Stories among other anthologies. His book The Perception of Meaning (Syracuse University Press, 2015) won the University of Arkansas Arabic Translation Award. Hisham was the 2017 recipient of the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Fellowship for Artists and Writers, and his second book in English translation, The Monotonous Chaos of Existence, is forthcoming in 2022 from Mason Jar Press. He occasionally tweets @H_Bustani.

Nariman Youssef (@nariology) is a Cairo-born, London-based semi-freelance translator with an MA in Translation Studies from the University of Edinburgh. She works between Arabic and English and part-time manages a translation team at the British Library. Literary translations include Inaam Kachachi’s The American Granddaughter, Donia Kamal’s Cigarette No. 7, contributions in Words Without Borders, The Common, Banipal magazine, and poetry anthologies Beirut39 and The Hundred Years’ War.

Rosie Barker is an illustrator and creative from the South of England who uses vibrant gradient colours and crisp linework to bring atmosphere and mood to her dream-like work. Her practice is often inspired by unusual landscapes, strange dreams, travel and the human psyche, which fuels her creative work for a range of clients from musicians to editorial advertising. When she’s not drawing from her attic room, she loves to travel, attend live music events, and find weird and wonderful items in second-hand shops. You can find her on Instagram.